Labor costs are sometimes overlooked. Overall, labor is often overly simplified in the mind of management because optimizing labor can be a science and an art incapable of being "solved" through broad-brushed layoffs or pushing it off into the corner to be ignored. Pricing pressure on suppliers, particularly in the consumer products space, has grown to the point that labor must be addressed. It is a key component of the manufacturing cost structure that can yield significant savings.

That art and science of labor optimization can be approached through a number of avenues:

- Automation of portions of the production process can remove labor from the equation, isolating the company from swings in labor availability and increasing the minimum/base wage

- Frozen/partially frozen production schedules allow for more careful planning of labor requirements

- Aligning machinery changeovers and preventive maintenance with breaks in the production schedule maximizes the utility of labor — both direct and indirect

- At least annually, seriously review labor standards by product and facility and ask why the standards could not be lowered

- Assess opportunities to use capital expenditure (CapEx) spending to address labor challenges and bottlenecks

- Use analytics and operational monitoring to determine where in the plant labor is more inefficient to zero in on certain departments, shifts, production lines, or crews that need to be addressed

- Where there is much difficulty in reducing labor costs, consider outsourcing or re-sourcing activities to address overall cost levels

Pursuing these initiatives requires a strong operational background and skill set and can be done in-house, with outside help, or with a combination of both. Whatever the decided approach, what is most important is that those involved work as efficiently as possible to realize the savings quickly while maintaining high service levels and manufacturing output. This requires a skillful balancing effort to keep processes going while driving significant change to operations, however it can be a game changer to the organization’s results.

Proponents of zero-based budgeting spread the message that there is no cost or program that is too sacred to get a free pass; every cost must be justified every single budgeting cycle. There is inherent business wisdom in considering every cost as a potential means to achieve cost reductions. Deeper review will rule some cost buckets out as less easily altered than others, but a company should consider all costs to reach profitability or cost goals. Companies across the consumer products sector are using or have publicly voiced their support of and interest in this approach to cost management, including Coca-Cola, Pilgrim’s Pride and Heinz.

These cost reduction goals may not be internally generated, however. Case in point — Wal-Mart. In 2015, this mega-retailer put pressure on its suppliers to reduce prices, as they themselves experienced pressure on earnings. The application of force to pricing puts the ball in the court of their suppliers, many of which are consumer products companies. The pressure on the suppliers is not coming solely in the form of price concession demands, but, as reported by Bloomberg, Wal-Mart asked thousands of its suppliers to "pay to use its distribution centers, warehouses and for shelf space in new stores."[1]

Often, consumer products carry narrow margins, particularly with the products sold to big-box retailers. If margins are already tight, it is unlikely that cutting them away completely would be a sound long-term proposition for the suppliers, leaving costs as the default field of play. Labor costs are a large cost component for many consumer products businesses and are in a state of flux as debates on the minimum wage and other employment measures and laws continue.

While pay levels of hourly workers in manufacturing environments are usually above minimum wage and retail pay rates, they are usually still considered to be "low cost." This fact can make managing labor costs a little more challenging because trends in those pay rates are billeted by various changes outside of their control, such as movements in the underlying minimum wage laws and wage levels of other industries employing low cost hourly workers. Beyond manufacturing, numerous other industries are heavily manned by lower cost employees, including hotels, restaurants and agriculture.

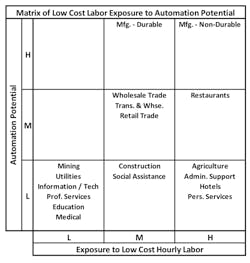

Labor expense can be addressed in numerous fashions. Consumer products businesses’ general focus on mass manufacturing lends itself well to one major lever in reducing labor costs and shifting some of the overall cost structure and exposure out of labor — automation. This is often a preferred option, as it directly counteracts the underlying exposure to changes in labor costs and can provide significant return on investment (ROI). The table below drops a sampling of industries into a matrix of two measures, the extent to which each is affected by lower cost employees and the prospect that they have to react via automation. Industries toward the upper right of the matrix will see increasing pressure to take advantage of the opportunity to automate.In many types of business, there is a misconception that there are no automation options for certain employee types or functions. For example, in many manufacturing operations, indirect hourly employees are often overlooked as a pool of labor that can flex in size along with underlying volumes or activity. In unfavorable labor environments, it is common to find that management believes themselves to be trapped in an environment in which they are stuck without recourse except to have the success of the enterprise suffer. However, when the baseline employee expenses increase drastically, the economics of capital investment to increase automation and reduce exposure to those labor costs are directly affected.

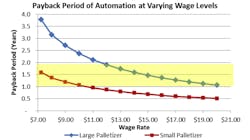

Depending on the specific sector, manufacturing can offer a wide array of automation opportunities. To calculate the effects of increases in underlying wage rates on the automation decisions, we zeroed in on a common and straightforward automation project found in many manufacturing environments — palletizing machinery. A palletizer eliminates the need for employees to stand at the end of production lines to do the very manual and often difficult job of stacking sometimes heavy boxes onto pallets in set configurations. Palletizers can be used across the consumer goods spectrum — from laundry detergent to snack foods.

To illustrate potential results of automation, we analyzed the effects on the payback period of investing in a large and small palletizing operation using manufacturing assumptions commonly found in consumer products manufacturing environments. The palletizer machinery replaces extremely manual jobs with machinery to stack boxes of finished goods onto pallets for storage or shipment. As the assumed wage rates increased, which would be the result of increases in minimum wages or the market for manufacturing labor, the payback period of the investment in the palletizers decreased significantly, making the decision to eliminate the manual palletizer positions more straightforward. For example, in the large palletizer scenario, when the wages of the related employees were set to $10 per hour, the payback period for this capital expenditure was 2.4 years. If the hourly wages rate was increased to $15, the payback period would fall by 38 percent to just 1.5 years, a payback term that is much more attractive to company management.Additional ways that manufacturers in the consumer products sector can optimize labor costs include the following:

- Flexibly and proactively manage direct labor. Activity/production schedules are not written in stone, and "frozen production schedules" are often susceptible to melting. Consider equipment breakdowns, raw-materials shortages, and last-minute rush orders, and it is apparent that flexibility is required to keep costs from soaring. A part of the strategy to have the operation flex with demand includes correctly employing employee overtime and temporary labor, improving production planning, and having labor crewing tools to ensure labor supply matches demand — every day, every shift, every hour.

- Align activities to minimize downtime and equipment changeovers. As in manufacturing, group the production of all products that can be run without requiring downtime for mold or other changeovers on the production lines. Once that related production group is completed, the next grouping of products should be run that requires the smallest amount of effort and cost to change over from the current tooling. This concept is referred to as the "production wheel," where the products cycled through production follow a sequence where changeover times are smallest. Companies do not always have an understanding of this concept or the data or tools to implement this best practice, but it can generate significant savings, in part because of the high costs of the skilled workforce often required for these machinery changeovers.

- Question the standards and budget the financials in multiple ways. The values used as benchmarks in planning, scheduling and evaluating are often stale or wrong. For example, without manual modification for the attributes of the specific company and its niche in the market, comparison with statistics from the broader industry will make for unreliable and unfair comparisons. Companies will roll incorrect standards forward from one year to another, rendering variance metrics nearly useless. In addition to evaluating and analyzing the standards, companies should create multiple versions of budgets to proactively plan ahead and steer the business through whatever labor scenario materializes.

- Reevaluate list of potential capital expenditure projects. The palletizing automation example above shows that increasing labor costs will change the equation on what proposed capital spending projects will clear internal CapEx hurdles. Take a second look at the projects in your company’s capital outlay pipeline and review operations to find additional opportunities to adjust the cost structure in response to increases in labor costs.

- Determine where employees or activities are not performing to standards or best practices. Through a barrage of tailored analytics, key performance indicators, employee and manager interviews, and real-time monitoring of activities, it is possible to identify where problem areas exist in an operation. Comparing and contrasting various parts of the process with those performing at the highest performance levels can begin the process of untangling the reasons for differences in performance — and also present opportunities for improvement.

- Try re-sourcing/outsourcing as a viable option. Consider re-sourcing your supplies and third-party services to help mitigate the potential increases in labor costs. For goods and services that have previously been produced internally, consider outsourcing them to third parties to find new ways to offset labor cost growth; other companies may be more effective in managing these cost changes, making outsourcing suddenly more attractive.

Re-approaching your company’s labor costs with the above considerations in mind will help management keep the effects of labor cost increases under control and your business viable. Pursuing these methods of cost control will demand cross-functional, top-down effort to successfully hunt down opportunities and then to maintain the resulting improvements. While often difficult, it is possible to accomplish these initiatives, and they have been put in place with great results within many organizations. The above list of best practices is just a sampling of the full gamut, but even this short inventory of options demonstrates that managing labor properly to maximize the output and costs is not simple, quick or easy. Labor management systems, well thought-out human resources policies, and very smart decisions on where CapEx dollars are spent are crucial to remaining competitive in the present and (especially) in the near future; the results and the security they bring to the organization are worth the labor they require.

Andrew Csicsila is a director in AlixPartners’ Performance Improvement practice and has over 20 years of consulting and industry experience in assisting organizations redefine their strategy and operations to drive higher bottom-line results and faster growth. His functional focus is on operational performance improvement through manufacturing efficiency, manufacturing strategy, process redesign and optimization of supply and manufacturing performance to lower-cost countries. Csicsila has worked across a broad range of industries and segments, gaining particular expertise in the consumer products, automotive and diversified manufacturing sectors. He has also conducted numerous value-enhancement programs for leading private-equity firms that have yielded long-term impact. He may be reached at [email protected].

Kevin Lucey is a vice president in AlixPartners’ Performance Improvement practice, who specializes in helping consumer and household product companies with major operational and strategic issues. His work has included numerous projects related to optimizing direct and indirect labor across dozens of manufacturing plants. He couples operational experience with a finance background to zero in on realistic solutions that add tangible value to the organizations. Other experience includes work around manufacturing and distribution footprint optimization, financial forensics, product profitability, business valuations and determining economic damages. He may be reached at [email protected].

[1] "Wal-Mart’s Suppliers Are Finally Fighting Back." Pettypiece, Shannon and Matthew Townsend. September 11, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2016.