Extractive distillation is a powerful technique for separating close-boiling and azeotropic mixtures. Understanding its mechanics and applications is essential as it becomes more prominent in industrial chemical processes worldwide.

Distillation separates liquid mixtures based on boiling point differences. However, conventional distillation cannot produce two pure products from a binary mixture with azeotropic systems. Extractive distillation effectively addresses these challenges. This article introduces the technology, discusses its mathematics and provides real-world examples.

Distillation 101

Distillation is a fundamental separation technique in industrial chemical processing. It exploits differences in boiling points to achieve high-purity separation of components within mixtures. It plays a crucial role in recovering and purifying products and solvents, essential for producing most commodity and specialty chemicals. While commonly used, conventional distillation methods encounter challenges with azeotropes and mixtures with closely spaced boiling points, often resulting in incomplete separations and inefficiencies.

Common types of distillation include simple, fractional and azeotropic. Simple distillation is effective for mixtures with significant boiling point differences. In contrast, fractional distillation employs a fractionating column for closer boiling points — azeotropic distillation targets mixtures forming azeotropes, where vapor and liquid compositions are identical. Distillation separates components based on volatility, whereas more volatile liquids with lower boiling points typically recover first. Despite its widespread application, the technique demands varying energy inputs across different boiling points. It necessitates specialized methods such as batch, continuous, steam stripping, high vacuum, reactive, extractive, azeotropic and pressure swing distillation. Azeotropic mixtures comprise components with constant boiling temperatures at which the liquid and the vapor compositions are equal at a given pressure, posing separation challenges not addressable by conventional distillation methods.1

What is extractive distillation?

Extractive distillation is a technique for separating components of azeotropic or close-boiling mixtures by adding a solvent. This solvent alters the relative volatilities of the initial components, disrupting the azeotrope and enabling the separation of previously inseparable components. For close boiling separations, the solvent can increase the relative volatility of the initial components.

Adding a solvent increases the difference in boiling points between components, enhancing the efficiency of the distillation process. Ideally, the solvent used has a higher boiling point than the feed components, making it easier to recover and reuse.

In extractive distillation, the solvent modifies molecular interactions within the mixture, distilling one component with high purity.2 Unlike azeotropic distillation, which forms a new azeotrope, extractive distillation avoids this by using a solvent that does not create a new azeotrope.1 This distinction makes extractive distillation easier to model and often preferable.

Alternative methods, such as pressure swing distillation, separate azeotropes by shifting azeotropic composition with pressure changes. However, these methods may be less than ideal due to high energy requirements, limited effectiveness across pressure ranges, and potential thermal instability at elevated pressures.

Mathematical approaches in extractive distillation

Understanding the key concepts of extractive distillation involves several fundamental principles. Raoult’s Law describes the vapor pressure of ideal mixtures as being proportional to their molar compositions in the liquid phase. At the same time, activity coefficients account for non-ideal behavior, which is crucial in distillation calculations. Mass and energy balances are essential for efficiently designing and operating distillation columns. The reflux ratio, the liquid returned to the top of the column to the distillate collected, is optimized to enhance separation. The McCabe-Thiele method, adapted for extractive distillation, considers the impact of added solvents on separation.

Key definitions include vapor pressure, which measures a liquid's tendency to evaporate, and partial pressure, which refers to the vapor pressure of a specific component in a solution. The activity coefficient (γ) represents the real-to-ideal partial pressures ratio. According to Raoult’s Law, the partial pressure of component A in an ideal solution is calculated as PA=xAP0A, where xA is the mole fraction of component A. For ideal gases, the partial pressure is PA=yAPT. In non-ideal systems, the activity coefficient modifies Raoult’s Law: PA=γxAP0A, leading to the equilibrium equation yA=.γxAP0/PT.

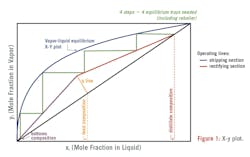

The vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) is depicted on an x-y plot, showing the concentrations of vapor and liquid in equilibrium at a constant pressure. This plot forms the basis for the McCabe-Thiele diagram, which includes a 45-degree line from the origin, the rectifying section operating line (ROL), the stripping section operating line (SOL), and the feed enthalpy line (q-line). These lines represent the mole fractions of the more volatile component throughout the column, starting at the bottom composition in the stripping section and ending at the distillate composition on the rectifying line and intersecting at the feed composition. By counting the steps between the intersections of the equilibrium curve and the operating lines, the number of theoretical stages required for a specified separation can be determined. In the McCabe-Thiele diagram below, four equilibrium trays, including the reboiler (if not a circulating type), are necessary. The operating lines are nearly straight due to the constant molar latent heat of vaporization. By optimizing these elements, extractive distillation can be effectively designed and operated.

The process

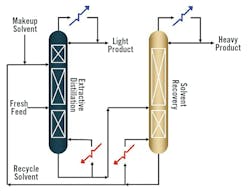

Extractive distillation is a complex process involving feed, solvent and distillate streams, where precise control of solvent addition points and column configurations is crucial. The feed stream contains the initial mixture to be separated, while the solvent stream is added to enhance the separation process, resulting in a high-purity distillate stream. In the first column, there are two separate feeds. The “fresh feed,” which contains the solution to be distilled, is added in the lower part of the column, and the solvent feed is added higher up in the column (Figure 2). Trays or packing within the column facilitate efficient vapor-liquid contact, optimizing separation efficiency. The top section of the column enables the separation of the low-boiling product from the high-boiling solvent. Temperature and pressure control play vital roles in maintaining effective operation.

Optimizing the solvent addition point is essential for achieving successful separation, with heating aiding component separation within the column. The solvent-to-feed ratio is adjusted based on the specific characteristics of the mixture. Typically, the extractive distillation process involves multiple columns but at least two columns, depending on the complexity of solvent recovery. The extractive distillation column includes distinct sections: solvent recovery (removing the solvent from the overhead product), rectifying and stripping, each crucial for concentrating components of varying volatility. In the recovery column, the solvent is recycled from the bottom, resulting in a relatively pure, heavy component distillate.

Criteria for solvent selection

When choosing a solvent for extractive distillation, it should selectively alter the partial pressure of specific components without interfering with the separation process due to its boiling point and volatility while remaining chemically stable and non-reactive towards the components. Commonly used solvents include Glycols, Glycerol, Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) and Dimethylformamide (DMF). There can be many choices for the solvent depending on the initial makeup of the feed to be separated. The solvent's boiling point ideally exceeds that of the "fresh feed" components, ensuring miscibility without forming an azeotrope. Additionally, the activity coefficients of the elements should be altered to change their relative volatilities. Evaluation often involves creating a McCabe-Thiele diagram (Figure 3) for the binary mixture with a fixed solvent concentration on a solvent-free basis. If the diagram suggests enhanced binary separation with solvent addition, further steps include process simulation and empirical pilot-plant studies. For example, Figure 3 illustrates that adding phenol as a solvent to an isooctane/toluene mixture can yield favorable outcomes in extractive distillation. The X-Y plot shows the initial binary equilibrium (green curve) and the equilibrium in the presence of 70% phenol solvent (blue curve).6 Solvents rank based on increasing relative volatility or selectivity, with the top-ranked solvent typically considered the most economically suitable for the separation task, ensuring the lowest total annual cost of the extractive distillation process.4

Applications of extractive distillation

Extractive distillation for R22 recovery from azeotropic refrigerant mixtures

A refrigerant producer in the Northeast engaged with a specialist to design a distillation system aimed at continuously recovering saleable R22 from an R22/R12 azeotropic refrigerant mixture. Overcoming the challenges posed by azeotropes such as R22/R12, the expertise in extractive distillation ensured effective separation. The client's existing column was integrated into the extractive distillation system, minimizing project costs, shaping the entire process design and incorporating instrumentation into a modernized control system. The process includes two primary stages: light removal, initially enriching the feed with R22 and R12, followed by extractive distillation using a proprietary solvent as an entrainer to break the R22/R12 azeotrope, achieving 99.5 wt% purity for R22 as the distillate stream of new extractive distillation column. R12 was removed from the solvent in the existing distillation column, and the solvent was recycled. Although operating below total capacity during extractive distillation, the client's column performed optimally in other modes, ensuring efficient operation adaptable to diverse process demands. The successful delivery of the system was on schedule and within budget, facilitating smooth startup and ongoing operation and supporting the recovery of high-purity R22, which is essential for U.S. systems that are still dependent on it as a refrigerant. With its versatility, the system remains poised for potential repurposing as industry requirements evolve.

Recovering and recycling low-boiling alcohols and ketones

A chemical processing facility sought to recover and recycle pure or denatured ethanol from an aqueous waste stream. The complex mixture of water, ethanol and trace amounts of other chemicals posed a significant challenge in achieving the required purity levels for ethanol reuse. Additionally, the facility needed to ensure that the resulting aqueous waste stream met stringent disposal regulations, minimizing the concentration of residual organics. Toxic chemicals such as benzene and cyclohexane were not considered for azeotropic distillation as even a tiny amount of these chemicals in the recovered alcohol would render the product unacceptable.

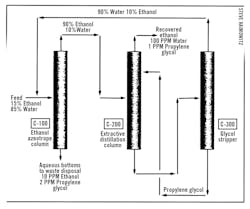

The facility implemented a modular extractive distillation system to address these challenges, as depicted in Figures 5 and 6. The system consisted of three key columns, each playing a critical role in the recovery process:

- Column C-100 (Figure 5): The first step involved stripping ethanol from the aqueous solution. This column was designed to produce 90-92 wt% ethanol as the distillate, while the bottom fraction contained water with only 10 ppm ethanol and 2 ppm propylene glycol. Lower concentrations of organics could be specified if necessary, but this level was generally sufficient for compliance with disposal standards. Additionally, any solids in the feed were retained in the C-100 bottoms, simplifying subsequent processing steps.

- Column C-200 (Figure 6): This extractive distillation column was the heart of the recovery process. It is operated by recycling propylene glycol within the column to maintain a sufficient concentration for effective separation. The column was divided into three sections: the middle section focused on rectifying alcohol by removing water, while the bottom section stripped ethanol from water. Although complete ethanol removal was not required, the process design accounted for any residual ethanol by recycling it through the C-300 column.

- Column C-300 (Figure 6): The final column in the system was responsible for stripping water and any remaining ethanol from the propylene glycol exiting C-200. The high relative volatilities of ethanol and water compared to propylene glycol made this separation more accessible. The clean propylene glycol was then recycled back into the process, ensuring minimal waste and maximum efficiency.

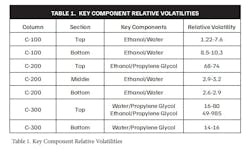

Table 1 provides the relative volatility ranges for key components in each column, which were calculated using computer process simulations. These simulations guided the optimization of the entire distillation system.

The modular extractive distillation system, as shown in Figures 5 and 6, delivered significant benefits to the facility:

- High-quality ethanol recovery: The system consistently produced ethanol at 90-92 wt%, suitable for internal reuse, reducing the need for purchasing fresh ethanol.

- Compliance with environmental standards: The process effectively minimized residual ethanol and propylene glycol in the aqueous waste stream, ensuring it met environmental disposal regulations.

- Operational efficiency: Computer simulations allowed the facility to optimize the design and operation of each distillation column, reducing operational costs and improving overall efficiency.

Closing

Extractive distillation is widely applied across various industries, such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals, petrochemicals and refining.3,4 Petrochemicals and refining efficiently recover aromatic hydrocarbons like benzene, toluene, and xylene from pygas, enhancing product purity and recovery rates while reducing solvent carryover risks and capital costs.3 Similarly, pharmaceutical and specialty chemicals facilitate solvent recovery, like isopropyl alcohol from wastewater, offering significant cost savings, waste reduction, and compliance with environmental regulations. Extractive distillation excels in separating close-boiling or azeotropic mixtures, maintaining solvents in a liquid phase, and often being more cost-effective than alternatives like pressure swing distillation. While not universally applicable, its advantages warrant consideration in complex distillation scenarios.

References

1. Gerbaud, V.; Rodriguez-Donis, I.; Hegely, L.; Lang, P.; Denes, F.; You, X. Review of Extractive Distillation . Process Design, Operation, Optimization, and Control. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 141, 229–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. Cherd.2018.09.020.

2. Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, S.; Bu, G. Control of Extractive Distillation and Partially Heat-Integrated Pressure-Swing Distillation for Separating Azeotropic Mixture of Ethanol and Tetrahydrofuran. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54 (34), 8533–8545. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs. Iecr.5b01642.

3. Gentry, J. C.; Kumar, Sam.; Wright-Wytcherley, R . Use Extractive Distillation to Simplify Petrochemical Processes; Advances in Solvent Technology Enable Using Extraction Methods to Separate Close Boiling Point Compounds Cost-E ectively. Hydrocarbon Processing. June 2004, p 62+.

4. Lei, Z.; Li, C.; Chen, B. Extractive Distillation: A Review. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2003, 32 (2), 121–213. https://doi.org/10.1081/SPM-120026627.

5. Schlowsky, G., Loftus, B., “Recovering and Recycling Low-boiling Alcohols and Ketones,” Chem Eng, February, 2000, pp.97-98.

6. Mass Transfer Operations, Second Edition. Robert E. Treybal, pp 393-395

About the Author

Alan Erickson

Vice president at Koch Modular

Alan Erickson is vice president at Koch Modular and a member of the executive team. Erickson brings over 40 years’ experience in process design, startup and project management of chemical manufacturing plants. Subject-matter expertise includes computer simulations of entire recovery plants, design of unit operations such as evaporation, distillation, liquid-liquid extraction, absorption and adsorption, heat transfer and fluid flow, complete process control systems and instrumentation. He is a Professional Engineer and holds a B.S. in chemical engineering from Rutgers University.