Combustible dust hazard identification and dust testing under NFPA 660

Dust-generating processes are integral to many industries that produce the foods we eat, the medicines we rely on, and many other items that we use daily. Combustible dust safety is an incredibly consequential factor in determining how facilities are designed and how safe those facilities are for workers while still providing production efficiency and continuity.

The first step to identifying combustible dust hazards in a facility is to review dust testing basics and guidance. Most processors are familiar with the connection between dust testing and completing a Dust Hazards Analysis (DHA), which is an OSHA requirement for many processes. Knowing what to expect from dust testing ensures that no unnecessary testing is performed and that accurate test results are achieved. In December 2024, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) released NFPA 660 Standard for Combustible Dusts and Particulate Solids. The standard includes new testing guidelines, which we’ll review in this article.

Figure 1 reviews the variety of dust tests that might be useful for your specific dust and application. Note that while NFPA is an important organization that releases combustible dust safety guidance for North America, many of the tests that NFPA prescribes rely on ASTM Standards for testing procedures.

The basic Go/No-Go test determines whether a dust/material is combustible and tells you whether you need to proceed with additional dust tests. As noted in the table, minimum ignition energy (MIE) is an essential data point that helps to determine the risk of ignition for a material. A material’s Pmax/KSt is needed to design explosion protection equipment, which could include explosion vents, flameless vents, and other explosion protection or mitigation equipment. Results from other testing options such as minimum ignition temperature of a layer are needed on a case-by-case basis and are more application dependent. Consult with experts during the DHA and dust testing processes to determine which tests will be most practical to identify hazards for your specific process.

How NFPA 660 impacts dust testing

The release of NFPA 660 has impacted how all industries must address dry bulk processing. This consolidated standard was created after years of collaboration by stakeholders and NFPA Technical Committee members to align the growing number of standards and provide a more streamlined structure that unifies terminology. Industry feedback had indicated that there were too many different standards and that some industries needed to reference multiple sources with slightly different information to accomplish their combustible dust hazard reduction efforts.

In Chapter 5.1 of NFPA 660, the standard notes that, “The owner/operator of a facility with potentially combustible dust shall be responsible for determining whether the materials are combustible or explosible.” This passage lays out the duty to identify hazards, which is a key step toward minimizing risk. In NFPA 660, some important new material evaluation steps are outlined in Section 5.3: self-heating, thermal instability, water reactivity, and chemical reactivity.

A self-heating hazard evaluation is recommended if one or more of the following conditions applies to your application:

- bulk storage or transport of combustible particulate solids in large quantities

- large amounts of material present in a dryer discharge bin and exposed to elevated temperatures

- identification of potential self-heating issues in a DHA

This hazard identification method can be performed by a documented review process of past experiences in storing and transporting the material in large quantities. The parameters for this testing should include that the bulk materials would be in comparable or larger quantities than those used in the facility, at temperatures comparable or higher than the expected temperature (whether in storage or transport), and for durations comparable to or longer than the expected storage or transport duration. These parameters ensure that the material is being assessed conservatively.

Laboratory tests must be conducted to determine self-heating potential and rate, with findings used to conduct a theoretically based scaling analysis that would define the material’s critical temperature for self-heating at the specific process facility’s scale.

A thermal instability hazard evaluation is recommended if one or more of the following conditions applies to your application:

- more than 2,200 pounds of a combustible particulate are stored for longer than 8 hours in a bin, hopper, or bulk pile at temperatures exceeding 104°F (30°C)

- more than 220 pounds of particulate materials are in an oven or dryer for more than an hour

- heated materials residing for an extended time in a process as identified in a DHA

This hazard identification method can be performed by a documented review process that relies on pertinent reactivity literature, safety data sheets, and operating experience. Reactivity and thermal decomposition onset temperature should be identified for processed materials, along with byproducts the reaction would create, including toxic, corrosive, or flammable gases. Any testing should be performed at the highest potential temperature the material could reach based on exposure conditions identified in a DHA.

A water reactivity hazard evaluation is recommended if one or both of the following conditions apply to your application:

- water-based fire suppression is used for the combustible particulate material

- particulate material or dust is exposed to process water, condensed water vapor, or outdoor precipitation

Importantly, NFPA 660 highlights that identifying a material’s incompatibility with water is a high priority since water is used in many plants for cleaning and is a primary method used in emergency response to combustion events.

This hazard identification method can be performed by a documented review process that relies on pertinent reactivity literature, reactivity screening software, and operating experience. Once reactivity is identified, byproducts, including toxic, corrosive, or flammable gases should be noted.

A chemical reactivity hazard evaluation is recommended if a particulate or dust could be exposed to an incompatible material or if a reactivity scenario is identified in a DHA.

This hazard identification method can be performed by a documented review process that relies on pertinent reactivity literature, reactivity screening software, and operating experience. Once reactivity is identified, byproducts, including toxic, corrosive, or flammable gases should be noted. Another option is to use calorimetry testing to determine chemical reactivity hazards.

The important takeaway from these new material testing guidelines is that NFPA 660 now accounts for the reactivity hazards for some bulk materials or particulates that have the potential to release energy or produce products that can be more ignitable than the original material. The additional risk factors reviewed for self-heating, thermal reactivity, water reactivity, and chemical reactivity are within the scope of a DHA.

Dust testing fundamentals for proper hazard identification

Dust testing is a practical and important step in understanding a combustible dust and determining the safety risks associated with that dust. Many well-known commodities have published data available, which can be used as a basis for a facility’s plans to mitigate dust hazards. However, accepting published data at face value can be a mistake if you do not ensure that the actual material being handled is similar. The risks around a given combustible dust depends on many factors, and even experts do not completely agree on which dust tests are required for a situation.

Besides dust test type, you must consider where in the process to collect that dust/material sample for testing. This means considering locations where the finest fraction of dust can be collected, which is often at the dust collector stage normally located at or near the end of the process.

Testing protocols for collected dust samples typically specify that the sample must be dry with less than 5 percent moisture by weight. This ensures that near worst-case scenario materials are tested. If moisture is controlled in your process and the material has a different moisture level, you may want to prioritize testing the materials nearer to actual process conditions. Note that it is a little-known fact that most dust explosions occur in the cold, dry winter months. If you are unsure what moisture level should be used, drying the material is often the best course of action.

When sending in a sample, another common question is whether the dust should be tested by the laboratory “as received” or whether it should be dried, reduced in size, and even classified to limit testing to the fines of that dust. Testing protocols encourage the effort to capture a worst-case result. If your process handles materials with tight control of both particle size and moisture content, testing material “as received” may be the better course of action. If not, taking the more conservative approach by further preparing the sample and following the protocols provided by ASTM is prudent.

The next factor to consider is whether the dust being handled is one single material or a mixture. Experts agree that mixtures pose several challenges, including that they may potentially contain dozens of ingredients. In that case, it is not practical to test every single component that comprises the entire mix. At a minimum, select and test the top five or six ingredients that represent the largest percentage of the mix.

Dusts that can change characteristics or degrade over time pose a special challenge, both in achieving a representative sample and packaging and shipping that sample to the lab. Metal dusts are an example of this because they oxidize quite readily and must be packaged in an airtight vacuum container and shipped quickly. Keep in mind that some dust samples cannot be air freighted for quick transport.

Dust sampling plans

NFPA 660 includes information on how to achieve a representative sample to comply with the requirements within the chapter. Sampling plans should include the following:

- identification of the location where fine particles and dust are present

- identification of representative samples

- collection of representative samples

- preservation of sample integrity (more on this later)

- communication with the test laboratory on sample handling

- documentation of samples taken

- safe sample collection practices

As noted, the sampling plan must preserve sample integrity. Samples collected should be from rooms and building facilities where combustible dust can exist. This can include rooms where mixing, conveying, screening, abrasive blasting, packaging, storage, and other processes are performed.

Where multiple processes and materials are present in an area, use worst-case samples in conjunction with a DHA to assess the hazards. Performance-based design allows the user to identify and sample select materials versus a prescriptive approach where all materials are collected and tested.

Where multiple pieces of equipment are present and contain essentially the same material, a single representative sample can be acceptable. However, note that attrition and separation based on particle size should be assessed. For example, when conveying a material on a belt conveyor, the material present on the conveyor belt is often different than the fines present along the sides or at the bottom of the conveyor. This means that one sample should be collected from the center of the conveyor and another should be collected from the fines generated during processing.

Materials that are to be used for screening tests and for the determination of material hazard characteristics, such as KSt, MIE, and other tests, should be collected from the areas or interior of equipment presenting the worst-case risk. Particularly hazardous processes such as grinding require further evaluation. Grinding can result in a wide range of particle sizes and combustible solids such as dusts, fibers, fines, chips, chunks, flakes, or a mixture of these particulate types. Grinding generates ever finer material, so it should always be considered for dust testing, regardless of the initial particle size.

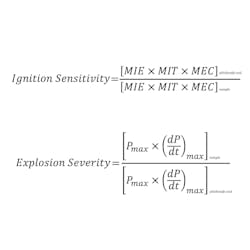

Once some initial testing has been completed on a material, a few hazard assessment formulas (as shown in Figure 3) can come in handy to determine a material’s ignition sensitivity (IS) and explosion severity (ES). Ignition sensitivity is used to quantify how easily a material ignites. Explosion severity is a method used to compare the magnitude of a deflagration. Once calculated, the IS and ES can be used to determine whether a dust is a Class II material. If the IS is < 0.2 and the ES is <0.5, a material is often considered to be not a significant dust explosion hazard.

Understanding the material is paramount

Considering the complexities involved in dust testing, it is understandable that many companies choose expert consultants who are familiar with combustible dust and the real-world hazards they pose. Understanding your material is of paramount importance as is knowing where the greatest risk lies in your process. To achieve the best testing results that lead to clear and actionable tasks, you must have a dust sampling plan, select meaningful dust tests for your application, and be prepared to interpret the results with knowledgeable experts (whether within your own safety team or from an outside consultant). Well-executed dust testing results provide the data needed to complete a DHA, maintain compliance with the latest industry regulations and standards, and keep plant workers safe.

CV Technology