Why food processors should consider ingredient transport systems

As of December 6, 2024, companies involved in processing food products are required to comply with NFPA 660 Standard for Combustible Dusts and Particulate Solids (2025). This single standard now includes all the fundamentals of the former NFPA 652 as well as the previous commodity-specific standards 61 (food), 484 (metals), 654 (all other), 655 (sulfur), and 664 (wood). For food processors, the new NFPA 660 standard chapters 1 through 10 and 21 provide the appropriate standards for combustible dust compliance.

Although the physical size of this standard may appear daunting, it offers a simpler and more concise compilation of the standards affecting any facility where combustible dusts are handled, processed, and/or produced. None of the committees providing combustible dust standards have disappeared; they now are concerned with specific chapters of NFPA 660 rather than separate documents. Therefore, the user of this new standard should not expect any major changes in the standards but hopefully more clarity and understanding of what is required for true combustible dust compliance.

This includes a unique set of standards exclusive to the food processing industry that allows the injection of a “dose of reality” concerning the hazards and risks involved in handling clean, processed, bulk materials. This approach to the conveying of a specific class of materials has been included in NFPA 61 since the 2017 edition (NFPA 660 represents a third cycle). This approach is known as the Ingredient Transport method for conveying specified food ingredients.

This unique set of standards can also be considered as the Ingredient Transport exemption. In this case “exemption” refers to establishing all the conditions necessary to allow the pneumatic conveying of specific materials from one location to another within a facility without the need for explosion and isolation protections typically associated with combustible dusts.

Years of accumulated empirical evidence has shown pneumatic conveying to be the single-most effective and safe method for conveying combustible particles and dusts from one location to another. Explosion or related events associated with these systems nearly always are associated with unforeseen circumstances or physical failure (e.g., conveying line breaks) rather than inherent hazards and risks associated with systems such as dust collection.

Ingredient Transport System requirements

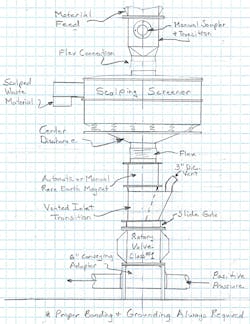

An Ingredient Transport System is defined as a vacuum or positive-pressure pneumatic conveying system (can be dilute, semi-dense, or dense phase) with a dedicated filter receiver (aka, Air-Material Separator or AMS) that is used to exclusively transport cleaned food ingredients or mixtures from storage or a similar source to another location within a facility (Figure 1). At first glance, this seems simple enough, but certain conditions must be met before this “exemption” can be applied.

An Ingredient Transport System that meets all the qualifications “shall be permitted to be installed without explosion protection.” However, that system must meet ALL the conditions and not just some of them. Those conditions are summarized as follows:

- The system must be either a positive or negative (vacuum) pneumatic conveying system. It does not matter if it is dilute, semi-dilute, or dense phase, but it must be limited to pneumatic conveying systems only.

- The system overall design must be such that it is ensured to be isolated from any possible ignition sources. This includes mechanical (e.g., bearings), electrical (e.g., control panels, exposed motors, switches, etc.), and electrostatic (e.g., propagating brush discharges). The methods used to provide this isolation can range from rotary airlock valves (must be Class 1 construction), sealed bins or hoppers (no leakage or equipment that can impair the seal/isolation), etc. This is obviously necessary to keep any reasonable possibility of a connected or immediately external device from creating a deflagration event.

- The system must be protected from any size-reduction (i.e., milling) operations, foreign material (all types), contamination, mechanical energy, electrical sparks or arcs and any viable or identifiable ignition source. Every precaution must be taken to ensure that no ignition source can become a viable hazard.

- The system cannot be for the pneumatic transfer of raw bulk grain. This is unprocessed and uncleaned raw bulk grain.

- The material’s Minimum Ignition Energy (MIE) must exceed 10 mJ. Materials with MIEs below this level are subject to an array of different electrostatic ignition sources, not all of which can be eliminated. Fortunately, it is rare for typical processed food products or ingredients to have an MIE below 10 mJ. The entire system must be fully bonded and grounded. Full continuity to an earthed ground must be proven and documented. This is to minimize the probability of higher-energy electrostatic discharges such as a propagating brush discharge.

These conditions, all of which must be met, inherently imply other typical operational conditions.

Examples are proper preventive maintenance, proper regular maintenance, adequate controls and monitoring devices to ensure that the system operates properly, etc.

It is important to also note that an Ingredient Transport System can be an existing or new system. Or it can be an existing system that is revised to achieve (and exceed) the previous conditions.

The key factor in all the conditions is the necessity of the conveyed material to be clean. This means the material must be 100% pure ingredients, or as close to that value as is achievable using available technology.

Ingredient Transport System implementation

The previously referenced Figure 1 shows a typical, simple, new Ingredient Transport System. The system utilizes the following to ensure that clean material is safely conveyed to the discharge point:

- A properly sized and selected scalping screener to remove contaminants, foreign objects, etc.

- A properly sized rare earth drawer-type magnet (manual or automatic) to remove metals and similar contaminants. It is critical that this is done just before the actual pneumatic transfer process.

- Filtered, clean air to vacuum convey the clean material to the filter receiver.

- A Class 1 rotary airlock valve to meter the received material into the mixer or bin and to provide isolation.

- Proper bonding and grounding of the entire system.

As previously stated, it is also possible to modify an existing pneumatic conveying system to meet (and hopefully exceed) the requirements for a successful Ingredient Transport system. In some cases, this is a simple and inexpensive process. In other cases, it is considerably more complicated.

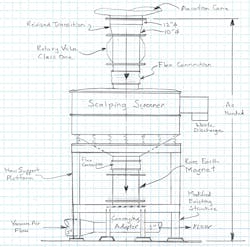

Figure 2 shows a filter receiver discharge through a Class 1 rotary valve, through a metal detector and into a pneumatic conveying vented (small dust collector with fan) hopper with Class 1 rotary valve and into a positive-pressure pneumatic conveying system to a surge bin (latter portion not shown). At first glance this grouping of equipment seems to achieve the requirements for an Ingredient Transport System. However, this system, as it exists, does not meet the requirements for the following reasons:

- No screening is provided to remove foreign material prior to the material flowing through the magnet. The magnet, alone, is not capable of ensuring uncontaminated, clean, material.

- The use of a small fan (not spark resistant) with a small dust collector, to vent the hopper feeding the pneumatic conveying system represents a viable ignition source. Such fans, even on the “clean” side of the filters have been known to create sufficient heat for embers, especially if the filters leak dust through the fan (which is not uncommon).

- There is no evidence of proper grounding and bonding.

This system, however, can be adapted to achieve the desired results. Figure 3 shows the revised system (including a manual sampler) that meets all the requirements for Ingredient Transport status.

Figure 4 shows a second existing system that would appear to be a candidate for an Ingredient Transport system. But again, this assembly does not qualify due to the following reasons:

- There is no rare earth magnet (or equal) to remove metals, etc.

- The flex connection provides no proper grounding or bonding.

- The filter receiver (not visible) does not have a Class 1 rotary valve for isolation.

Figure 5 shows how this assembly can be modified to achieve Ingredient Transport status. By raising the screener and locating the new magnet below and by providing proper transitions, bonding, and grounding, the assembly can provide the clean material to the filter receiver. However, a Class 1 rotary valve is required at the receiver discharge to isolate the unit from ignition sources below.

The Ingredient Transport exception, Section 21.9.4.3.1.3 in NFPA 660, is not a “carte blanche” for any pneumatic conveying system for food processing ingredients. Skipping portions of the requirements will only lead to increased risks and unwanted legal liability should an event occur.

Scrupulously following the requirements and limitations does not fully guarantee that some random fire, flash fire, or explosion event will not occur. No system, even with full prescriptive protections, can fully guarantee combustible dust safety under all conditions, known or unknown. However, experience has shown that Ingredient Transport systems, when properly done, result in conditions that both mitigate and minimize the hazards and risks involved.

About the Author

Jack Osborn

Senior Project Engineer

Jack Osborn is senior project engineer at Airdusco EDS and a member of Processing’s editorial advisory board. He has more than 50 years of experience in dust collection systems, centralized vacuum cleaning systems, pneumatic conveying systems, and all types of bulk handling systems. He has either designed or evaluated (e.g., engineering studies/audits, performance testing, etc.) more than 2,000 dust collection systems during his career and is a participating member of all six NFPA combustible dust committees.