How to clean and sanitize piping in pneumatic conveying systems

Pneumatic conveying is a process where dry materials are transferred through piping from one point to another. The nature of the system involves enclosed pipelines, which are both versatile and secure. However, the same attribute that provides these advantages (enclosed piping) also makes it relatively inaccessible. For many systems, the material passes cleanly and effectively and there is no need to interact with the internals. In other cases, the material can begin to build up like cholesterol (e.g., titanium dioxide) on the pipe wall, which will eventually need to be addressed. In other cases, the cleanliness of the process demands that each device be cleaned and sanitized on a regular basis to ensure product safety (e.g., baby formula). When cleaning is required, the piping must either be removed and cleaned manually, or a process must allow the pipes to be cleaned in place. This article discusses the needs and processes to clean in place.

CIP

Historically, clean-in-place (CIP) refers to a wet process in which piping of any sort has design and fittings to allow a caustic solution to be pumped through it as a way to dissolve and wash any contamination. This type of wet cleaning is rarely implemented in pneumatic conveying applications because the nature of the process is dry. Although it is possible to merge the dry and wet processes, the fittings, couplings, elbows, etc., are different enough that conflicts arise in the design stage and special facilities are required at the plant level. It is also not viable to retrofit a wet cleaning solution into an existing system. Therefore, the remainder of this article focuses on dry cleaning and sanitizing options.

Cleaning and sanitizing

The need to clean or sanitize will vary by application. Some users will be intervening in a preventive way to keep their processes operational, and others will be cleaning as part of a plant Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plan in order to ensure product safety. Across this range of need, the approach will be divided into three categories:

- System compatibility — How well the system and components promote cleaning

- Cleaning — The removal of material from the piping system

- Sanitizing — Providing a kill step to ensure remediation of living organisms

Depending on the product and process needs, emphasis will be placed in some or all of these areas in order to create a whole solution.

System compatibility

When trying to implement a cleaning or sanitizing solution, the condition of the system with respect to its components plays a large role in whether or not the solution can be implemented. A new system can be designed with this thought in mind and the components selected in kind. An existing system must be analyzed to determine whether or not it conforms to the basic requirements that facilitate the cleaning. Below are a few of the highlights for consideration:

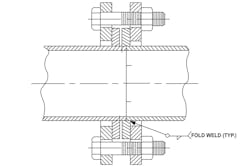

Couplings — The couplings that hold the pipe together can be critical to the effectiveness. A basic compression coupling will hold a modest amount of pressure but do little to ensure pipe joint integrity (gaps where the pipes join). Flanged fittings will raise the pressure rating significantly but the basic gasket still provides recesses where material accumulates. The ideal coupling for cleaning purposes provides a flush metal joint and contains a recessed gasket out of the material flow area (see Figure 1). The type and number of couplings will play a large part in determining the implementation and effectiveness of the solution.

Figure 1. The ideal coupling for cleaning purposes provides a flush metal joint and contains a recessed gasket out of the material flow area.

Pipe diameter — Particularly when discussing mechanical cleaning, the consistency of the pipe inside the diameter will affect the cleaning. Some pipes change diameters in order to control velocity while others utilize flex hose that does not exactly match. A mechanical cleaning device trying to apply stress to the pipe wall will not work if the pipe

diameter changes.

Other components — Since there are often other piping components that make up a piping system, each of these components will need to be analyzed for compatibility. Airlock adapters, knife gates and diverter valves are common examples, and each will have a range of manufacturers and designs. The main concern will be how the pipe transitions in and out of the device and how well the pipe size is maintained.

Cleaning

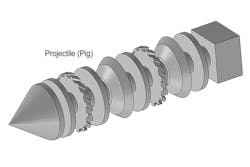

Physical cleaning of pipe internals is difficult due to the enclosed nature and relative inaccessibility of the pipe. Removing the pipe and cleaning offline is possible but it is time- and labor-intensive. Cleaning pipes in place is generally done using a projectile called a "pig" that scours the pipe wall as it travels (see Figure 2). In liquids and oil/gas, high-pressure (4–6 Bar) is used to drive the pig. Using pressure of this magnitude with a compressible gas (air) creates risk with the fast-moving projectile and shifting volumes of high-pressure air. Therefore, in a pneumatic conveying system, the operating pressure of the pig should be controlled to operate < 1 Bar. A special pig design may be required to strike a balance between cleaning effectiveness and motive pressure requirements.

Figure 2. A projectile is used to clean pipes and drive contamination out

of the system.

Other features of a pigging process involve delivery and retrieval of the pig (launching and catching). Depending on the frequency of cleaning, the launching of the pig can be automated to greater and lesser degrees. If a process must be halted hourly in order to clean, then automating the launch will have a significant return on investment in the form of minimized downtime. A different process that is only cleaned monthly during planned downtime can use a more manual launch method. In both cases, the launching equipment will be custom-fabricated to fit the need. Providing a method to catch the pig should be considered in all cases. This method may be a dedicated piece of equipment but must include a way to safely vent the motive air and provide accessibility to retrieve the pig itself. Understanding how to effectively launch, drive and catch the pig will make pigging an effective in-place pipe cleaning solution.

Pneumatic conveying lines

Sanitizing

For processes that must consider the implications of microbial growth, it may be necessary to add a sanitizing step to the cleaning process. Sanitizing the internal pipe surface is similarly difficult due to the inaccessibility. A sanitizing medium must be chosen that can be applied to the pipe surface and is validated to reduce the log count of contaminating organisms. Ozone gas is a high-oxidizing agent that can be generated locally from compressed air and then injected into a convey line. By raising the ozone concentration inside the pipe to lethal levels (for organisms) and maintaining the exposure for a validated time period, the internal pipe surface can be considered sanitized.

Another sanitizing medium widely used is heat. The internal temperature of the pipe can be elevated by heating the convey air volume (while the system is not in use). A temperature gradient will form based on heat exchange properties with the environment. It may be necessary to add insulation to the pipe to limit the heat loss so reasonable inlet temperatures can be used. It is also necessary to raise the humidity of the heated air stream. The "dry heat" is not as effective because some microbes become dormant and will revive when the treatment ceases. Moist heat is validated to create significantly greater log reductions by comparison. Process controls should be put in place to tightly control the heat and humidity levels because crossing the dew point of the coolest pipe surface generates condensation and freestanding water.

Ozone gas and moist heat are not the only methods to sanitize pipes; however, these methods have been validated to produce certain kill rates. These also have the desired attribute of being easily purged once the treatment is finished. The convey pipe is able to be used within minutes of the treatment end with no further effort as well as no residue left on the pipe wall. Altogether, once the system is compatible with these processes, in-place cleaning and sanitizing can be implemented in a functional and effective manner.

Jonathan Thorn is executive director, Process Technology, at Schenck Process, a global source of highly accurate dry bulk solids pneumatic conveying, weighing and feeding systems with additional expertise in air filtration.