Going green 1 milliwatt at a time

In the past, we believed we had a nearly infinite amount of natural resources with endlessly progressing technology that could be used to create anything at our fingertips. Now we know that we have limited natural resources, and some technologies, once cutting edge, are known to be harmful to people and the environment. We have come a long way in our efforts to help protect the environment, but every little bit counts, and we can always do more. One way that Otek has taken steps to help the environment came when it reconsidered the powering of the digital bar meter.

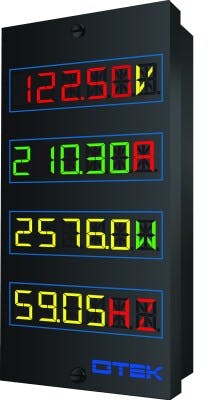

A digital panel meter with alphanumeric display | All images courtesy of Otek Corporation

Analog equipment

Analog meters are the industry’s most energy-efficient meters. They function using the energy in the signal that they measure. However, they are sensitive to wear and tear, shock, and vibration. The meters, although inexpensive, can be inaccurate and unreliable. These deficiencies may cause problems when used in airplanes, ships and nuclear power plants. When they read zero, operators cannot tell if the signal is dead or if the needle is stuck. As a result, operators may ignore a meter at zero. Because they are inexpensive and easy to connect, many industries still rely on them.

Digital meter power consumption

The digital counterparts of analog meters, digital panel meters, make up for most of the analog equipment’s deficiencies. Not having moving parts, digital panel meters are more durable and reliable. They have high digital accuracy and are easily read by operators using human machine interfaces. Some units can communicate with supervisory control and data acquisition/distributed control systems via serial input/output (I/O) (machine-to-machine interface). Some units are available, which control the process they measure. These meters require external power, on average at least 2 to 10 watts (W). For the last several years, digital bar meters have been consuming more and more energy in proportion to this increase in functionality.

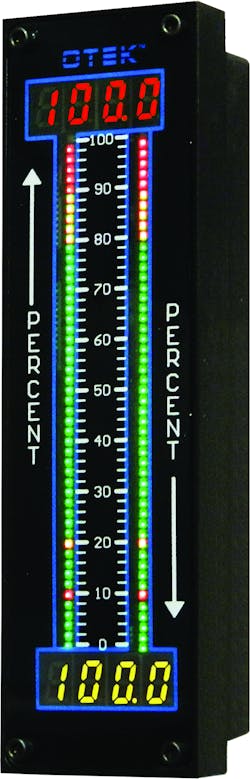

This meter features automatic signal fail-detection.

Nuclear power plant conversion

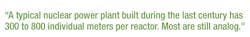

The digital meters had all the benefits the industry was looking for, but at what cost? The meters did not conform to pre-existing equipment, requiring a more complicated installation. A typical nuclear power plant built during the last century (1960 to 1980) has 300 to 800 individual meters per reactor. Most are still analog.

Replacement of analog meters would require reworking of panels, new wiring and engineering designs, agency approvals, and inspection and operator training. Plants would have to supply additional power for normal operation and emergency power sources such as battery banks. Planning and implementation for these replacements could take more than three years to complete. If approximately 500 analog meters were to be replaced with traditional, digital units, assuming they only require the average 5 W to operate, the new power source would have to produce and store more than 2,500 W per hour. The typical cost of the conversion was estimated to be more than $20,000,000.

When told this by a nuclear expert, Otek experts decided to make developing an alternative for analog-to-digital conversion its priority. While designing the industry’s first 100 percent signal-powered [alternating-current (AC) or direct-current (DC)] digital meter, the development team thought of a barge going downstream using the energy of the flow of water and realized a lot of free energy flows all around us. Even the water flowing from a garden hose generates energy. Processes inherently have their own energy, typically about 100 milliwatts (mW). This energy is wasted because most meters require 1 to 10 W to operate, so power had to be drawn from another source. A way to apply this wasted energy needed to be discovered.

The goals were simple. The new meters needed to be signal driven, like an analog meter, and to reproduce the needle of the analog units. The design also had to be something that was easy to mount and connect by incorporating a mechanical design that was a “drop-in replacement” for either analog or digital meters.

The units would also need to be interference free and computer compatible (isolated serial I/O), all while maintaining accuracy, reliability and durability. This technology needed to include the benefits of the two existing technologies, be plug and play, and add something innovative.

100 percent signal power

Current loop (4-20 and 10-50 mA DC)-powered digital panel meters had been developed and patented by Otek in the 1970s and incorporated in the new design of the New Technology Meters (NTM) series. The challenge was to signal power the units with the AC signal – just like the analog meters.

The team needed to design an ultra-efficient current transformer (CT) so that the meter could use the free energy for power without saturating the customer’s CT and thereby eliminate the need for external power. A typical 5 amp CT is used to measure AC/power along with volts AC. By designing a highly linear and efficient miniature CT, the meter could extract the power of the AC line to power the electronics for volts, amps, watts and frequency.

The team began additional development of this new technology only to be brought to a standstill. Certain components it needed to accomplish this goal simply were not yet available.

The new technology

As a result of new developments and inventions from other creators, NTM was designed using ultra-efficient, custom LEDs that require about 1⁄100 of the energy that a standard LED uses. The team included a parasitic, application-specific, integrated circuit that uses approximately 1 percent of the energy of a regular microcontroller. The engineers developed software to efficiently share the 10 to 100 mW of power available. This is a 99 percent reduction in energy use. With all these new innovations, the NTM uses existing energy to operate (provided the signal can produce more than 10 mW). The team was able to accomplish the same objective as Sir R. Weston when he created the analog meter in 1893 but for modern applications. Imagine if the “footprint” could be reduced by 99 percent.

With the puzzle of how to use less energy to operate the meters solved, the team needed to design needle representation. When stopped at a traffic light, the lead engineer had an epiphany: Why not copy the universally accepted “red, yellow and green” traffic light standard? Red was known to imply danger, yellow inevitably stood for caution and green represented safety. This design was incorporated into a bar graph for the meter that would display color setpoints and alarms.

A one-channel digital panel meter

The new technology design was already a superior alternative, still the lead engineer felt that more could be added. The team included an alarm to notify operators when the signal failed. How can a “dead” meter detect and record the occurrence? A battery was considered. However, this would limit the meter’s practicality. In certain segments of the market, a battery could be hazardous. Approximately 100 mW of energy were needed. This energy would last long enough to visually display a message while sending serial data to the central computer. A new energy storage device was designed. With it, excess energy from the signal detects when the signal goes dead and enables the alarm to indicate an input fail.

The end result of approximately 40 years of persistence is new technology that replaces the fit, form and function of the 1893 analog meter and the 20th century digital meter. Most importantly, the meter will ensure added safety with built-in input failure detection. Operators will no longer have to guess the status of their processes or the status of their meters. With a meter capable of so many things, it could help prevent additional accidents.