Pneumatic conveying system keeps powder kept dry

When thoughts turn to efficiency in machine design, it bears noting that the human body includes some of the best-automated systems around. The circulatory system, for example, contains chambers and valves that efficiently direct blood from the heart to the organs and body extremities and back to the heart at a regular rate appropriate for "production demands." Aside from operator error or faulty hardware somewhere down the line, the circulatory system requires little or no on-going maintenance.

In the world of manufacturing, many an engineer seeks the same clockwork-like regularity and effortless operation. Ramsey, N.J.-based Okonite Co., a producer of premium insulated wire and cable since 1878, found something much like that in a custom-designed pneumatic conveying system that "keeps the area clean, the powder contained within the system and minimizes the amount of waste we have at the end of the day," says Chris Wagner, director of facilities engineering, Okonite.

This particular operation at the Orangeburg, S.C. plant uses a proprietary three-step process to coat wire cable with super-absorbent polymer (SAP) that serves as a blocking agent so water cannot run inside the conductor, if the insulation is breached in an underground or wet environment.

Process parameters

While this fine powder is very effective at protecting wires — and therefore systems from shorts — in production it is prone to gumming up with exposure to moisture. Exposure of SAP to the humid air of South Carolina can in itself cause clumping, and just like cholesterol build up in a heart, this can affect production efficiency.

What actually happens is that the plant runs between 400 and 600 feet of cable per minute through a four-foot long atomizer chamber that blows the SAP around in a cloud that coats the wires. Before turning to pneumatic conveying, an in-house system with a single-filter housing captured product for reuse. But each time the filter needed cleaning the chamber would switch from negative to positive pressure. Powder would escape through the holes where the cable entered, exit the chamber and be released into the plant.

"When we contacted VAC-U-MAX, our goal was to make the system truly negative, to reclaim the product and remove excess air," says Wagner. "We needed to control the environmental end of the process and that is exactly what they did. It is a focused application," he says.

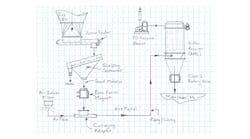

The dual-conveyor system with automatic changeover supplied by VAC-U-MAX works much like a beating heart. The Belleville, N.J.-based company designs and manufactures custom pneumatic conveying systems built around standards and assembles systems using stock equipment.

Cable enters into a chamber at about 400-600 feet per minute while an atomizer simultaneously injects positive air and SAP into the chamber wherein it coats the cable fibers. At that same time, the dual-conveyor system sucks air out of the coating chamber at a faster rate than it enters, creating the negative pressure system whereby SAP cannot escape.

At this point, the material enters into the first of two valved chambers for a matter of seconds. Then the first valve closes while the second valve and chamber open. When the first valve is closed, air is blasted into the filter to release any particulates to the bottom of the system, where another routing system returns the SAP back into the hopper for reuse. This filtration cleaning process is repeated for a few seconds until the first filter is entirely clean, and then the second valve closes for its own identical process.

A breeze, pneumatically speaking

What seems like a complicated procedure is rather simple to an expert pneumatic conveying manufacturer. "We just told them how much powder we were moving, the cubic feet per minute, and how much powder we were wasting on the over-spray. They put in a filter that was big enough to reclaim it," notes Wagner.

"We were losing about 7% of our material per shift with our former system. The VAC-U-MAX system has brought that loss down to nearly zero," Wagner says.

A bag unloading station was supplied to further remove moisture from the system and reduce SAP particles escaping into the plant environment. Instead of releasing into the air, the material is removed before it has a chance to enter the air.

"The bag unloading station that we have now does a much better job than before, without clogging up the powder in the system. It is healthier for the operators," says Wagner. "It’s all integrated to this reuse system so it doesn’t go into a wasted dust collector; it goes into a reuse dust collector."

Maintaining the health of a heart requires little maintenance, save eating and exercising such that its passageways don’t get clogged. Machinery in a plant should also require only the same kind of commonsense care.

The long view

Wagner explains that what little maintenance the system needs is made very simple by having a mezzanine, above the coating chamber, where the VAC-U-MAX system is housed.

"The system works flawlessly and performance is maintained by following recommended periodical maintenance, just changing filters at recommended intervals."Maintaining a good working relationship with the supplier has also been without effort. "We ran a couple tests at their plant before they shipped it and everything worked as specified," notes Wagner. Implementation went as expected, and VAC-U-MAX expeditiously addressed any issues that arose.

He concludes: "Everything they said they could do for us, they did."

Marisa Zocco is a technical writer based out of Long Beach, Calif.